2018Q3 Reports: Program Chairs

Program Committee

Organising Committee

General Chair

- Claire Cardie, Cornell University

Program Chairs

- Iryna Gurevych, TU Darmstadt

- Yusuke Miyao, National Institute of Informatics

Workshop Chairs

- Brendan O’Connor, University of Massachusetts Amherst

- Eva Maria Vecchi, University of Cambridge

Tutorial Chairs

- Yoav Artzi, Cornell University

- Jacob Eisenstein, Georgia Institute of Technology

Demo Chairs

- Fei Liu, University of Central Florida

- Thamar Solorio, University of Houston

Publications Chairs

- Shay Cohen, University of Edinburgh

- Kevin Gimpel, Toyota Technological Institute at Chicago

- Wei Lu, Singapore University of Technology and Design (Advisory)

Exhibits Coordinator

- Karin Verspoor, University of Melbourne

Conference Handbook Chairs

- Jey Han Lau, IBM Research

- Trevor Cohn, University of Melbourne

Publicity Chair

- Sarvnaz Karimi, CSIRO

Local Sponsorship Chair

- Cecile Paris, CSIRO

Local Chairs

- Tim Baldwin, University of Melbourne

- Karin Verspoor, University of Melbourne

- Trevor Cohn, University of Melbourne

Student Research Workshop Organisers

- Vered Shwartz, Bar-Ilan University

- Jeniya Tabassum, Ohio State University

- Rob Voigt, Stanford University

Faculty Advisors to the Student Research Workshop

- Marie-Catherine de Marneffe, Ohio State

- Wanxiang Che, Harbin Institute of Technology

- Malvina Nissim, University of Groningen

Webmaster

- Andrew MacKinlay(acl2018web@gmail.com), Culture Amp / University of Melbourne

Area chairs

- Dialogue and Interactive Systems:

- Asli Celikyilmaz Senior Chair

- Verena Rieser

- Milica Gasic

- Jason Williams

- Discourse and Pragmatics:

- Manfred Stede

- Ani Nenkova Senior Chair

- Document Analysis:

- Hang Li Senior Chair

- Yiqun Liu

- Eugene Agichtein

- Generation:

- Ioannis Konstas

- Claire Gardent Senior Chair

- Information Extraction and Text Mining:

- Feiyu Xu

- Kevin Cohen

- Zhiyuan Liu

- Ralph Grishman Senior Chair

- Yi Yang

- Nazli Goharian

- Linguistic Theories, Cognitive Modeling and Psycholinguistics:

- Shuly Wintner Senior Chair

- Tim O'Donnell Senior Chair

- Machine Learning:

- Andre Martins

- Ariadna Quattoni

- Jun Suzuki Senior Chair

- Machine Translation:

- Yang Liu

- Matt Post Senior Chair

- Lucia Specia

- Dekai Wu

- Multidisciplinary (also for AC COI):

- Yoav Goldberg Senior Chair

- Anders S?gaard Senior Chair

- Mirella Lapata Senior Chair

- Multilinguality:

- Bernardo Magnini Senior Chair

- Tristan Miller

- Phonology, Morphology and Word Segmentation:

- Graham Neubig

- Hai Zhao Senior Chair

- Question Answering:

- Lluís Màrquez Senior Chair

- Teruko Mitamura

- Zornitsa Kozareva

- Richard Socher

- Resources and Evaluation:

- Gerard de Melo

- Sara Tonelli

- Karën Fort Senior Chair

- Sentence-level Semantics:

- Luke Zettlemoyer Senior Chair

- Ellie Pavlick

- Jacob Uszkoreit

- Sentiment Analysis and Argument Mining:

- Smaranda Muresan

- Benno Stein

- Yulan He Senior Chair

- Social Media:

- David Jurgens

- Jing Jiang Senior Chair

- Summarization:

- Kathleen McKeown Senior Chair

- Xiaodan Zhu

- Tagging, Chunking, Syntax and Parsing:

- Liang Huang Senior Chair

- Weiwei Sun

- Željko Agić

- Yue Zhang

- Textual Inference and Other Areas of Semantics:

- Michael Roth Senior Chair

- Fabio Massimo Zanzotto Senior Chair

- Vision, Robotics, Multimodal, Grounding and Speech:

- Yoav Artzi Senior Chair

- Shinji Watanabe

- Timothy Hospedales

- Word-level Semantics:

- Ekaterina Shutova

- Roberto Navigli Senior Chair

Main Innovations

PC co-chairs mainly focused on solving the problems of review quality and reviewer workload, because they are becoming a serious issue due to a rapidly increasing number of submissions while a limited number of experienced reviewers is available.

- New structured review form (in cooperation with NAACL 2018) to address key contributions of the reviewed papers, strong arguments in favor or against, and other aspects (see also below under “Review Process”). Sample review form was made available to the community in advance: https://acl2018.org/2018/02/20/sample-review-form/

- Overall rating scale changed from 1-5 to 1-6, where 6 stands for “award-level” paper (see details below under “Review Process”).

- The role of PC chair assistants filled by several senior postdocs to manage the PC communication in a timely manner, draft documents and help the PC co-chairs during most intensive work phases.

- Each area has a Senior Area Chair responsible for decision making in the area, including assigning papers to other Area Chairs, determining final recommendations, as well as writing meta-reviews, if necessary.

- Each Area Chair is assigned around 30 papers as a meta-reviewer. They are responsible for their pool in various steps of reviewing, e.g. checking desk-reject cases, chasing late reviewers, improving review comments, leading discussions, etc. This made the responsibility of area chairs clear and the overall review process went smoothly.

- The “Multidisciplinary” area from previous years was renamed to “Multidisciplinary / also for AC COI” to make sure Area Chairs’ papers will be reviewed in this area in order to prevent any conflict of interest

- Weak PC COI (e.g., groups associated with the PC through graduate schools or project partners) were handled by the other PC. Program chairs’ research groups were not allowed to submit papers to ACL in order to prevent any COI.

- A bottom-up community-based approach for soliciting area chairs, reviewers, and invited speakers (https://acl2018.org/2017/09/06/call-for-nominations/)

- Toronto Paper Matching System (TPMS) has been used since ACL 2017, while this year we used TPMS also for assigning papers to area chairs (as a meta-reviewer) and have encouraged the community to create their TPMS profiles.

- Automatic checking of the paper format has been implemented in START. Authors were notified when a potential format violation was found during the submission process. This significantly reduced the number of desk rejects due to incidental format violations.

Submissions

An overview of statistics

- In total, 1621 submissions were received right after the submission deadline: 1045 long, 576 short papers.

- 13 erroneous submissions were deleted or withdrawn in the preliminary checks by PCs.

- 25 papers were rejected without review (16 long, 9 short); the reasons are the violation of the ACL 2018 style guideline and dual submissions.

- 32 papers were withdrawn before the review period starts; the main reason is that the papers have been accepted as the short papers at NAACL.

- In total, 1551 papers went into the reviewing phase: 1021 long, 530 short papers.

- 3 long and 4 short papers were withdrawn during the reviewing period. 1018 long and 526 short papers were considered during the acceptance decision phase.

- 258 long and 126 short papers were notified about the acceptance. 2 long and 1 short papers were withdrawn after the notification. Finally, 256 long and 125 short papers appeared in the program. The overall acceptance rate is 24.7%.

- 1610 reviewers (1473 primary, 137 secondary reviewers) were involved in the reviewing process; each reviewer has reviewed about 3 papers on average.

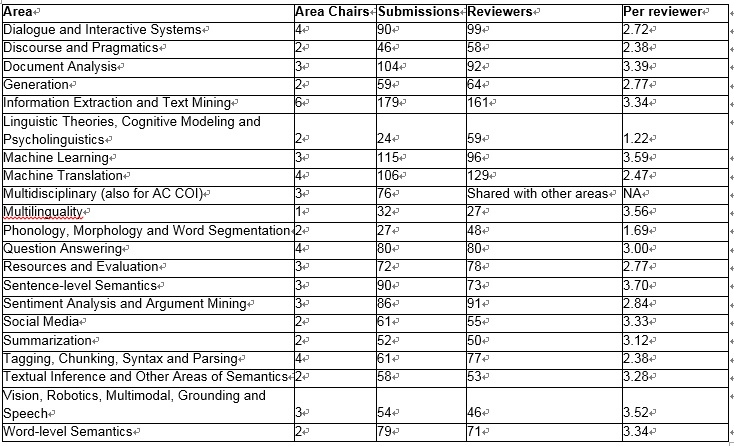

Detailed statistics by area

Review Process

Reviewing is an essential building block of a high-quality conference. Recently, the quality of reviews for ACL conferences has been increasingly questioned. However, ensuring and improving review quality is perceived as a great challenge. One reason is that the number of submissions is rapidly increasing, while the number of qualified reviewers is growing more slowly. Another reason is that members of our community are increasingly suffering from high workload, and are becoming frustrated with an ever-increasing reviewing load.

In order to address these concerns, the Program Co-Chairs of ACL 2018 carefully considered a systematic approach and implemented some changes to the review process in order to obtain as many high-quality reviews as possible at a lower cost.

Recruiting area chairs (ACs) and reviewers:

- Recruit area chairs (Sep - Oct 2017): the programme co-chairs (PCs) first decided on a list of areas and estimated the number of submissions for each area, and then proposed a short list of potential candidates of ACs in each area. Candidates who have accepted the invitation constitute the AC committee.

- Look for potential reviewers (Sep - Oct 2017): PCs sent out reviewer nomination requests in Sep 2017 to look for potential reviewers; 936 nominations were received by Nov 2017. In addition, PCs also used the reviewers list of major NLP conferences in previous one or two years and ACs nominations to look for potential reviewers. Our final list of candidates consists of over 2000 reviewers.

- Recruit reviewers (Oct - Dec 2017): the ACs use the candidate reviewers list to form the shortlist for each area and invite the reviewers whom ACs selected. 1510 candidates were invited in this first round, and ACs continued inviting reviewers when they needed.

- After the submission deadline: several areas received a significantly larger number of submissions than the estimation. PCs invited additional ACs for these areas, and also ACs invited additional reviewers as necessary. Finally, the Program Committee consists of 60 ACs and 1443 reviewers.

Assigning papers to areas and reviewers:

- First round: Initial assignments of papers to areas were determined automatically by authors’ input, while PCs went through all submissions and moved papers to other areas, considering COI and the topical fit. PCs assigned one AC as a meta-reviewer to each paper using TPMS scores.

- Second round: ACs looked into the papers in their area, and adjust meta-reviewer assignments. ACs send a report to PCs if they found problems.

- Third round: PCs made the final decision, considering workload balance, COI and the topical fit.

- Fourth round: ACs decided which reviewers will review each paper, based on AC’s knowledge about the reviewers, TPMS scores, reviewers’ bids, and COI.

Deciding on the reject-without-review papers:

- PCs went through all submissions in the first round, and then ACs looked into each paper in the second round and reported any problems.

- For each suspicious case, intensive discussions took place between PCs and the corresponding ACs, to make final decisions.

A large pool of reviewers

A commensurate number of reviewers is necessary to review our increasing number of submissions. As reported previously (see Statistics on submissions and reviewing), the Program Chairs asked the community to suggest potential reviewers. We formed a large pool of reviewers which included over 1,400 reviewers for 21 areas.

The role of the area chairs

The Program Chairs instructed area chairs to take responsibility for ensuring high-quality reviews. Each paper was assigned one area chair as a "meta-reviewer". This meta-reviewer kept track of the reviewing process and took actions when necessary, such as chasing up late reviewers, asking reviewers to elaborate on review comments, leading discussions, etc. Every area chair was responsible for around 30 papers throughout the reviewing process. The successful reviewing process of ACL 2018 owes much to the significant amount of effort by the area chairs.

When the author response period started, 97% of all submissions had received at least three reviews, so that authors had sufficient time to respond to all reviewers' concerns. This was possible thanks to the great effort of the area chairs to chase up late reviewers. A majority of reviews described the strengths and weaknesses of the submission in sufficient detail, which helped a lot for discussions among reviewers and for decision-making by area and program chairs. (See more details below.) The area chairs were also encouraged to initiate discussions among reviewers. In total, the area chairs and reviewers posted 3,696 messages for 1,026 papers (covering 66.5% of all submissions), which shows that intensive discussions have actually taken place. The following table shows the percentages of papers that received at least one message for each range of average overall score. It is clear that papers on the borderline were discussed intensively.

Structured review form

Another important change in ACL 2018 is the structured review form, which was designed in collaboration with NAACL-HLT 2018. The main feature of this form is to ask reviewers to explicitly itemize strength and weakness arguments. This is intended…

- …for authors to provide a focused response: In the author response phase, authors are requested to respond to weakness arguments and questions. This made discussion points clear and facilitated discussions among reviewers and area chairs.

- …for reviewers and area chairs to understand strengths and weaknesses clearly: In the discussion phase, the reviewers and area chairs thoroughly discussed the strengths and weaknesses of each work. The structured reviews and author responses helped the reviewers and area chairs identify which weaknesses and strengths they agreed or disagreed upon. This was also useful for area chairs to evaluate the significance of the work for making final recommendations.

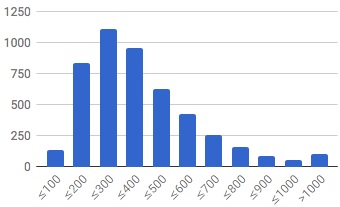

In the end, 4,769 reviews were received, 4,056 of which (85.0%) followed the structured review form. The following figure shows the distribution of word counts of all reviews. The majority of reviews had at least 200 words, which is a good sign. The average length was 380 words. We expected some more informative reviews – we estimated around 500 words would be necessary to provide strength and weakness arguments in sufficient detail – but unfortunately we found many reviews with only a single sentence for strength/weakness arguments. These were sufficient in most cases for authors and area chairs to understand the point, but improvements in this regard are still needed.

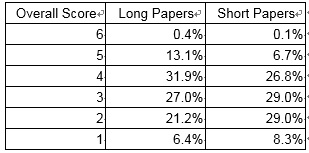

Another important change was the scale of the overall scores. NAACL 2018 and ACL 2018 departed from ACL’s traditional 5-point scale (1: clear reject, 5: clear accept) by adopting a 6-point scale (1: clear reject, ..., 4: worth accepting, 5: clear accept, 6: award-level). In the ACL 2018 reviewing instructions, it is explicitly indicated that 6 should be used exceptionally, and this was indeed what happened. (See the table below.) This had the effect of changing the semantics of scores, and, in contrast to the traditional scale, reviewers tended to give a score of 5 to more papers than in previous conferences. The following table shows the score distribution of all 4,769 reviews (not averaged scores for papers). Refer to the NAACL 2018 blog post for the statistics for NAACL 2018. The table shows that only 13.5% (long papers) and 6.8% (short papers) of reviews give “clear accepts”; more importantly, the size of the next set (those with overall score 3 or 4) was very large --- too many to include in the set of accepted papers.

Another new feature of the review form was the option to "Request a meta-review". This was intended to notify area chairs to look into the submission carefully, as the reviewer’s evaluation was problematic for some reason (e.g., the paper had potential big impact but was badly written). In total, 274 reviews contained a request for a meta-review. For these cases, the area chairs read the paper in depth by themselves when necessary.

Review quality survey

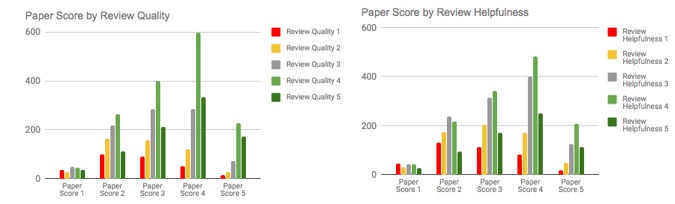

The Program Chairs asked the authors to rate the reviews. This was mainly intended for future analysis of good/bad reviews. The following graphs show the relationship between overall review scores (x-axis) and survey results (review quality and helpfulness). It shows review quality/helpfulness scores tend to be higher for high-scoring papers (probably authors appreciated high scores), while low-scoring papers also still received a relatively high percentage of positive review quality/helpfulness scores.

More detailed in-depth analysis will be conducted in a future research project. Also, reviews and review quality survey results will be partly released for research purposes in an anonymized form.

Review process

In this section, we describe the detailed process of reviewing and decision-making.

0. After the submission deadline, Program Chairs checked each paper’s area assignment and adjusted it, if necessary; this process included clear desk rejects (undebatable formatting violation or obvious conference mismatch). In order to prevent conflict of interest (COI) of Area Chairs, all papers with possible COI were moved to a designated area (“Multidisciplinary/COI”).

1. After the submission deadline, the Senior Area Chairs assigned an Area Chair and reviewers to each paper.

The Program Chairs determined the initial assignments of Area Chairs to each paper using the Toronto Paper Matching System (TPMS). The Senior Area Chairs adjusted the assignments themselves as necessary.

Next, the area chairs assigned at least three reviewers to each paper. This process employed TPMS and reviewer bidding results, but the area chairs determined final assignments manually, considering the specific research background and expertise of the reviewers, and the maximum number of papers that a reviewer could be assigned.

2. After the review deadline, the Area Chairs asked the reviewers to improve reviews where necessary.

Each Area Chair looked into reviews of their assigned papers and asked the reviewers to elaborate on or correct reviews when they found them uninformative or unfair. This was also performed on receipt of author responses (during the discussion phase).

3. After the author response period, the Area Chairs led discussions among reviewers.

The Program Chairs asked the Area Chairs to initiate discussions among reviewers when necessary. In particular, they asked reviewers to justify weakness arguments when they were not clearly supported. As shown above, a lot of discussions happened during this phase, helping reviewers and area chairs to more deeply understand the strengths and weaknesses of each paper. See the “Statistics” section for the effect of author responses and discussions.

4. After the discussion period, the Area Chairs produced a ranked list of submissions.

The Program Chairs asked the area chairs to rank all submissions in their area. They explicitly instructed them to not simply use the ranking resulting from the average overall scores. Instead, the Program Chairs asked the area chairs to consider the following:

- The strengths and weaknesses raised by reviewers and their significance;

- The result of discussions and author responses;

- The paper’s contribution to computational linguistics as a science of language;

- The significance of contributions over previous work;

- The confidence of the reviewers;

- Diversity.

Area chairs were asked to classify submissions into six ranks: "award-level (top 3%)", "accept (top 15%)", "borderline accept (top 22%)", "borderline reject (top 30%)", "reject (below top 30%)", and "debatable". They were also asked to write a meta-review comment for all borderline papers and for any papers that engendered some debate. Meta-review comments were intended for helping the Program Chairs arrive at final decisions, and were not disclosed to authors. However, we received several inquiries from authors regarding the decision-making process by area chairs and program chairs. Providing meta-review comments to authors in the future might help to make this part of the review process more transparent. If this process is adopted, then the area chairs should be instructed to provide persuasive meta-reviews that explain their decisions and that can be made accessible to the authors.

5. The Program Chairs aggregated the area recommendations and made final decisions.

The Program Chairs analyzed the recommendations from area chairs to make the final decisions. They were able to accept most "award-level" and "accept" papers, but a significant portion of "borderline accept" papers had to be rejected because the "accept" and "borderline accept" together already significantly exceeded the 25% acceptance rate. The Program Chairs analyzed the reviews and meta-review comments to accept papers from the "borderline accept" and occasionally the "borderline reject" ranks, calibrating the balance among areas. When necessary, they asked the area chairs to provide further comments. A significant number of papers (including "debatable" papers) remained until the very end, and the Program Chairs read these papers themselves to make a final judgment.

The Program Chairs also closely examined the papers satisfying the following conditions, in order to double-check the fairness of decisions:

- Decisions in contradiction with the area chair recommendations (e.g., papers rejected although the area chairs recommended "borderline accept");

- Accepted papers with an average overall score of 4 or less;

- Rejected papers with an average overall score of 4 or more.

In the future, all papers meeting these criteria should require a meta-review, along with some kind of explanation on how to improve the work as well as an acknowledgement of the work that went into the rebuttal.

Statistics

In the end, we accepted 256 of 1018 long papers, and 125 of 526 short papers (2 long and 1 short papers were withdrawn/rejected after acceptance notification). This makes the acceptance rate: 25.1% for long papers, 23.8% for short papers, and 24.7% overall.

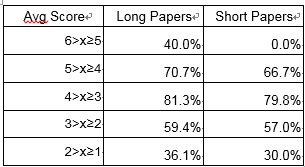

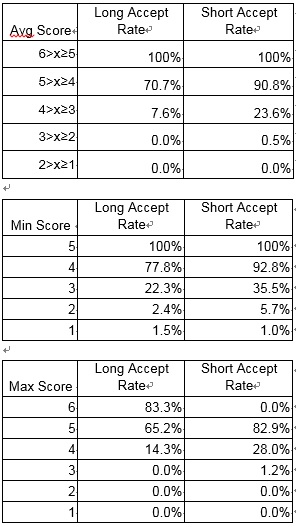

While we instructed the area chairs not to rely on average overall scores, obviously there should be some correlation between overall scores and acceptance. The following tables show acceptance rates for each range of overall scores. It shows that ACL 2018 was very competitive, as many papers with an average overall score of 4 or higher were rejected. However, it also shows that some papers that received a low score also got accepted, because area chairs looked into the content of papers rather than relying only on the scores.

In addition, some areas had a lot of high-score papers, while some others did not, so such effects were factored in by the Program Committee chairs when making the final decisions.

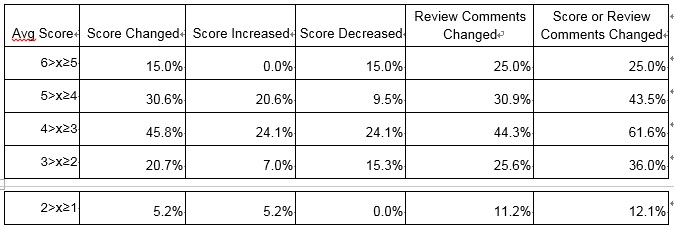

The following table shows how the scores or comments of each review changed after the author response and the discussion phase. Around half of the papers on the borderline received some change in scores and/or review comments.

Author responses were submitted for 1,338 papers. Of these papers, 685 (51.2%) saw some change in scores and/or review comments. Such changes also occurred for 24 of the 206 (11.7%) papers without an author response. This indicates that author responses have an effect on changing scores/reviews (although not necessarily positively).

Best paper awards

ACs selected top papers in their areas (zero to infinity) which satisfied as many as possible from the following conditions: of high quality, nominated by at least one primary reviewer, bringing disruptive groundbreaking innovation towards the current mainstream. ACs re-read their finalists and discussed among themselves the merits of the nominee's work with the help of the primary reviews. The candidates were submitted to the Program Co-Chairs to set-up START for reviewing by the Best Paper Committee. The Best Paper Committee (BPC) included 22 established senior researchers. BPC bid on papers and each paper was reviewed by 3 BPC members. The finalists were then selected upon long and thorough deliberation. The PC chairs have worked very hard to select papers reflecting different types of contributions to the field of CL as well as rewarding nicely conducted short papers as a valuable form of reporting focussed research results, among other criteria.

Best Long Papers

- Finding syntax in human encephalography with beam search. John Hale, Chris Dyer, Adhiguna Kuncoro and Jonathan Brennan.

- Learning to Ask Good Questions: Ranking Clarification Questions using Neural Expected Value of Perfect Information. Sudha Rao and Hal Daumé III.

- Let’s do it “again”: A First Computational Approach to Detecting Adverbial Presupposition Triggers. Andre Cianflone,* Yulan Feng,* Jad Kabbara* and Jackie Chi Kit Cheung. (* equal contribution)

Best Short Papers

- Know What You Don’t Know: Unanswerable Questions for SQuAD. Pranav Rajpurkar, Robin Jia and Percy Liang

- ‘Lighter’ Can Still Be Dark: Modeling Comparative Color Descriptions. Olivia Winn and Smaranda Muresan.

Presentations

- Long-paper presentations: 36 sessions in total (6 sessions in parallel), duration: 25 minutes per talk including questions

- Short-paper presentations: 12 sessions in total (6 sessions in parallel), duration: 15 minutes per talk including questions

- Best-paper presentation: 1 session on the last day

- Posters: 18 sessions in total (6 sessions in parallel), poster sessions are not parallel to talks, each day there is one slot for posters from 12.30 to 14.00

Timeline

February 22nd, 2018: Submission Deadline (Main Conference)

March 27th, 2018: Submission Deadline (System Demonstrations)

March 26th–28th, 2018: Author Response Period

April 20th, 2018: Notification of Acceptance

May 11th, 2018: Camera-ready Due

July 15th, 2018: Tutorials

July 16th–18th, 2018: Main Conference

July 19th–20th, 2018: Workshops

Issues and recommendations

The ACL community is growing, and we need more mature and more stable conference structures. For the various steps of the reviewing process, this includes: i) process automation where appropriate, and combining expert and machine intelligence, ii) increasing the manpower and streamlining the workforce for reviewing.

We have found the following innovations to be particularly beneficial:

- Introducing a hierarchical PC structure, specifically the roles of

- PC Co-Chair Assistants,

- Senior Area Chairs;

- Restricting the workload of each Area Chair to a maximum of 30 papers;

- The use of TPMS for rough reviewing assignments to ACs and reviewers;

- The use of automatic formatting checks before paper submissions;

- Having Area Chairs propose acceptance decisions based on a qualitative analysis of the reviews (as opposed to scores) and write meta-reviews for the majority of borderline papers;

- Structured review forms with strength/weakness arguments.

Suggestions regarding paper submissions and review process:

- [easy] Get rid of the submission ID in the style template. There is no practical need for it, but it requires authors to submit twice (because the ID is known only after the first submission).

- [easy] Provide direct access to the template on the GitHub page https://github.com/acl-org/acl-pub - maybe provide a direct download link in the README.md file (also with a version, such as “acl2019-latex-template-v1.0.zip”, where each version corresponds to the GitHub release). Raise awareness about this repository, so that bugs should be reported here and will be fixed (there was for example a bug with URLs causing compilation errors in NAACL’18 - people get frustrated when the process is not transparent: https://twitter.com/tallinzen/status/941760724308840449 ) This is in the responsibility of publication chairs.

- [medium] Clarification for supplementary materials: separate file, or appendix to the main file? This should be clarified very explicitly in advance.

- [easy/to be considered] It’s 2018 and we have nice tools such as Overleaf for writing in LaTeX without the hassle of installing it. Even non-computer-scientist people are able to use it right away. Let’s get rid of the Word template altogether. It’s causing trouble in deciding, whether the paper still fits the template or not (older Word versions might do bad things to a paper).

- [hard] Make a clear strategy with SoftConf how to prevent server choking around the submission deadline. Around the deadline, SoftConf crashed, and people do complain, of course. PCs have no technical capabilities to solve it but as ACL is paying for the service, this cannot happen; the total number of papers is in hundreds/thousands, so there must be a technical solution. This is annoying for a computer science conference.

- [medium] SoftConf might implement institutional COI function to make things easier. Currently email domains are used for COI detection, but many people register alternative emails (e.g. gmail) and it missed many COIs.

- [medium] SoftConf might implement an interface for authors to communicate with area chairs (like a discussion board).

- [medium] Allow the authors to access the rebuttal text after acceptance decisions for the authors’ reference.

- [medium] Allow to update dual submission information after the ACL deadline, because submissions to future conferences cannot be declared in some cases.

- [easy] Possibly nominate an emergency area chair, if any of the area chairs becomes unavailable.

The Program Chairs also encountered a number of issues that should be addressed as a community-wide effort for further improving the quality of the review process and conferences. The following areas require the attention of the community in the future.

- Reviewing infrastructure

- Implementing more automatic support for various steps of the reviewing process as part of a reviewing infrastructure; keep in mind that implementing new features in SoftConf takes time and usually cannot be done ad-hoc. Also consider the division of work between SoftConf and offline scripts, and the effective interface between them (e.g. easy-to-use interface for downloading/uploading data from/to START, a shared repository for review infrastructure scripts).

- Better support for COI handling, including professional conflicts. This requires maintaining reviewer/author information (e.g. affiliation history, co-author information). It should also be worth considering to introduce the role of a compliance officer.

- Better support for plagiarism detection, which can find significantly paraphrased plagiarism. It should support importing unpublished papers (assuming authors should submit all papers under review with overlapping content).

- Storing author/reviewer information. This should be extremely useful at least for review assignment and COI detection. This requires prior consent and proper handling of personal data.

- A framework to share knowledge and information about the reviewing process among *ACL conferences. In many cases, Program Chairs had to re-invent the wheel.

- Better integration of START and TPMS, e.g., automatically incorporating previously published papers into TPMS.

- Review quality and workload

- We found structured review forms and author response forms are useful for ACs/PCs to recognize strengths/weaknesses of papers given mixed levels of reviewers. However, it is also stressful for reviewers to see review forms varying conference to conference, and to be forced to get used to new forms. It is necessary to develop a concise and effective structured review form and use it consistently for *ACL conferences.

- Sharing criteria and data for selecting good reviewers, to reduce bad and late reviews. We collected review timestamp information and obtained prior consent to provide this information to future conferences. This can be a first attempt to use review information for selecting reviewers.

- Incentive to make the reviewing more rewarding.

- Measures to provide training and guidance for graduate students involved in reviewing papers as main reviewers – e.g., mentoring by their PhD advisors and/or area chairs.

- Reducing the reviewing effort caused by dual submissions to multiple conference in parallel.

- Having area chairs write persuasive meta-reviews to be provided to the authors to ensure the transparency of the final decisions and the future improvement of a paper.

- Submission policy and research ethics

- Imposing very strong expectations regarding the reproducibility of each paper’s results by making the data and the software available and easily executable (preferably they should be made publicly available, but at least must be available to reviewers and Program Chairs).

- Introducing the officer (shared among all *ACL conferences) for handling complaints about research fraud. Solving such cases requires a significant amount of sensitive effort and goes far beyond the role and capacity of program chairs.

- Clearer guidelines regarding the overlap with parallel submissions, between short and long version of the same paper, non-archival conferences (e.g., LREC), etc. to prevent from salami-slicing (the current guidelines of >25% overlap is very vague).

- Clarifying the anonymization policy. The current guideline does not explicitly prohibit putting URLs, software names, etc., which obviously break anonymity.

- Clarifying the role of supplement/appendix: how to handle anonymity in appendices (such as URLs, etc.), how to prevent from including important information there (a few authors seemed to have moved important content to appendix to save space, which caused a lot of trouble in reviewing).

- Others

- Possibly accepting more high-quality papers to the conference. Having to decline high-quality papers due to the lack of space in the conference is frustrating to the authors.

- Possibly designing a policy to allow authors who could not attend a conference due to an unavoidable reason (e.g. visa issues) to present the work at another *ACL conference.

Overall, ACL conferences are super-competitive, and many very good papers cannot be accepted since the conference space is limited. On the one hand, keeping the acceptance rate under 25% is important for structural reasons like top conference rankings. On the other hand, more inclusive strategies are needed to accommodate more papers qualifying for acceptance which would otherwise have to be rejected.

ACL 2018 Program Co-Chairs

Iryna Gurevych, TU Darmstadt

Yusuke Miyao, National Institute of Informatics